1880-1950’s, Early Beginnings

Georges Claude, demonstrating OTEC, 1926

The concept of using the ocean’s thermal difference to generate electricity was first proposed by French physicist Jacques d’Arsonval in 1881. Georges Claude was one of d’Arsonval’s students. In 1928, Claude built a test OTEC plant using the warm water effluent from a power plant in Ougrée, Belgium. Two years later he built a 22 kW open-cycle land-based plant in the Bay of Mantanzas, Cuba that operated for 11 days before the cold-water pipe was destroyed in a storm. In 1935, he attempted to build a floating plant off the coast of Brazil but stopped after unsuccessfully attempting to attach the cold-water pipe. In 1940, Claude proposed a land-based OTEC plant to the French government to be located at Abidjan, Ivory Coast. They laid the cold-water pipe and planned to began full construction in 1956, but the project was abandoned when a nearby hydroelectric dam came into service.

One of the engineers on the Abidjan project, Bryn Beorse, brought OTEC research to the University of California for the purpose of desalinization, where he built three open-cycle OTEC models. He became an important and vocal proponent of OTEC in the US until his death in 1980.

1960-1970’s, The Andersons

Article by the Andersons

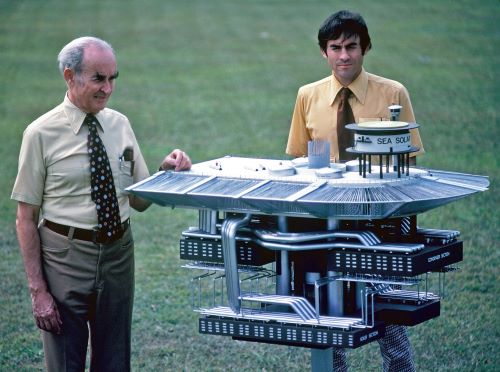

Anderson’s OTEC demonstration model

Anderson’s Sea Solar Power plant model

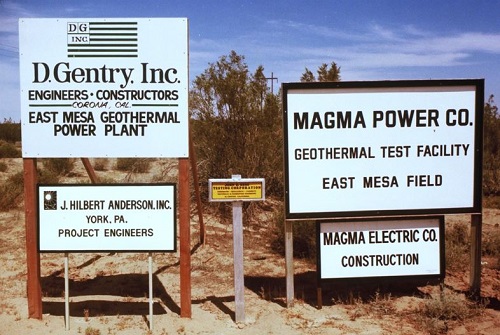

Anderson’s geothermal plant design

Anderson’s geothermal plant design

In 1959, J. Hilbert Anderson, chief engineer at the York Corporation, a refrigeration company, and former “Manhattan Project” member, began to research OTEC, establishing his own consulting company in 1962. His son, James Anderson, Jr., also joined in the research, and in 1963 submitted his Mechanical Engineering thesis at MIT, proposing an OTEC plant off the Florida coast. Seeing how Claude’s open cycle could be improved upon, in 1967 the father and son patented a closed-cycle OTEC plant system using propane as a working fluid. The open OTEC cycle became known as the “Claude Cycle” while the closed OTEC cycle became known as the “Anderson Cycle.” This was followed by 18 more patents related to OTEC.

The Andersons began a public campaign promoting OTEC, writing or being written about in Power Magazine (1964), an ASME technical paper (1965), the cover article for Mechanical Engineering (April, 1966), Forbes (April 15, 1972), The New York Times (April 22, 1974), Business Week (January 19, 1976), New Engineer (November 1976) the front page of The Wall Street Journal (November 22, 1976), The Washington Post (October 29, 1978) as well as myriads of local newspapers, from Hawaii to Houston, Baltimore, Columbus, and their hometown of York, Pennsylvania. In 1977 the duo demonstrated OTEC to the US Congress by turning on lights using only hot and cold water, and in 1979 J. Hilbert testified to a US Senate energy subcommittee about being ready to build an operational plant. J. Hilbert Anderson’s widespread influence as a proponent of OTEC was noted by The Washington Post’s Mark Swann in a 1978 article, where he noted Mr. Anderson was “known to the general public as the father of ocean thermal energy conversion, or OTEC”.1

In 1973, the Andersons began Sea Solar Power, Inc. to focus on designing an OTEC plant along with all the necessary components. They quickly realized that for OTEC to be a competitive energy source the core components of plant layout, energy cycle, heat transfer and turbine design would need to be specifically focused towards OTEC and not repurposed from other industries.

The Andersons began a public awareness campaign within government circles, highlighting OTEC’s potential. In 1972 Hilbert Anderson addressed the National Science Foundation’s Solar Energy Panel regarding this topic. The following year the US Energy Research and Development Administration (ERDA) launched an OTEC program, eventually spending over $200M on conceptual, environmental, and feasibility studies. They confirmed that OTEC is technologically and commercially viable, and ERDA’s successor, the Department of Energy, invited private industry to take over.

To display the principles behind OTEC, the Andersons built the first ever closed-cycle demonstration model which featured refrigerant being boiled and condensed by warm and cold water, with a small turbine/generator either powering automotive lights or producing hydrogen through electrolysis. In 1977 the Andersons demonstrated this OTEC model before Congress.

During the 1970s, OTEC was gaining the attention of the US government and industry, including several large companies. Global Marine Inc. (a large oil-drilling firm owned by Howard Hughs), Lockheed Martin and TRW (the predecessor of TRW Automotive, Northrop Grumman, Goodrich Corp., and indirectly, SpaceX), Bechtel, Hydronautics, Batelle and others along with university experts began programs to develop OTEC. Regardless of all this investment into research across industry, in 1977, Dr. David Mayer, a proponent of OTEC from the University of New Orleans, said that J. Hilbert Anderson, in his view, had the best “viable design” for an OTEC plant.2

Though government OTEC funding largely bypassed the Andersons in favor of large companies, their work in Sea Solar Power gained the attention of Barkman McCabe, known by many as the “father of the geothermal industry”. McCabe’s company, Magma Power, had found the area of East Mesa in Southern California to have resources of geothermal hot water. Because the current technology was only for harvesting power from geothermal steam and not hot water, he contracted the Andersons to design a power plant using the technology they developed for OTEC, as the principles were similar to those of OTEC.

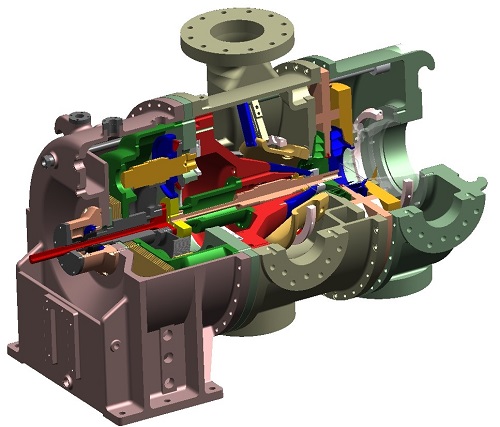

The Andersons designed a 11 MW plant using the principles they developed at Sea Solar Power. A turbine had to be designed specifically for this plant as no hydrocarbon turbines of this type existed. McCabe offered $10,000 to anyone who could find errors in the design, though none could. In 1979 the first commercial-sized closed-cycle geothermal plant came on line. Given the unique design components, it was the most efficient closed-cycle geothermal plant put in service to this day.

1 “Producing Electricity from Hot Water”, Mark Swann, The Washington Post, October, 29, 1978.

2 Shamcher: A Memoir of Bryn Beorse and His Struggle to Introduce Ocean Energy to the United States, page 16.

1980-2000

Mini-OTEC

OTEC-1

In 1980, President Carter signed the Ocean Thermal Energy Conversion Act into law, authorizing funds to be poured into OTEC research. These funds, however, were directed to large companies, with Lockheed Martin, the US Navy, Makai Ocean Engineering and others collaborating to build the first closed-cycle floating demonstration plant, named mini-OTEC.

The following year Global Marine, with funding from the Department of Energy, refitted a surplus Navy T-2 tanker to test OTEC heat exchange. This was called OTEC-1. Both mini-OTEC and OTEC-1 were short-lived demonstrations of the technology.

Japan entered the OTEC scene with the Tokyo Electric Power Company building a closed-cycle plant on the island of Nauru in 1981, being the first to send OTEC power (30 kW) to the public grid.

By 1998 the price of oil bottomed at $10/barrel, and OTEC lost its incentive as an economical energy resource. The Andersons, however, kept developing the Sea Solar Power design with their own private funding.

2000-2020

SSP vacuum pump

Saga University’s IOES

Makai 100 kW land-based plant

Okinawa 100 kW land-based plant

KRISO 1 MW floating plant

In 2001, Sea Solar Power entered into a 20-year licensing agreement with the Abell Foundation, who agreed to market and fund development of OTEC using Sea Solar Power’s technology. Abell’s focus was a 10 MW land-based plant to produce both electricity and fresh water. In 2004, Abell halted further development of SSP’s technology until a purchase agreement with a power utility had been reached, which unfortunately, failed to materialize.

In 2002, an Indian attempt to test a 1 MW floating plant failed when the cold-water pipe was dropped during assembly.

In 2003, Japan’s Saga University opened their Institute of Ocean Energy (IOES), complete with a combination OTEC/desalinization plant that produces 30 kW net power and 10 tons of fresh water per day.

In 2006, Makai Ocean Engineering, in coordination with Lockheed Martin, constructed an OTEC Heat Exchanger Test Facility at the Natural Energy Laboratory of Hawaii. In 2015 they added a turbine and completed the power cycle to provide 100 kW to the local power grid.

In 2016, Japan’s Okinawa Prefecture built a 100 kW land-based plant on Kume Island and connected it to the grid.

In 2019, the Korea Research Institute of Ships and Ocean Engineering (KRISO) built a 1 MW OTEC barge, producing a net power of 338 kW, the largest OTEC demonstration to date.

2021 – Present

Sea Solar Power 20 MW plant model

Presently, stepwise initiatives are being pursued by many across OTEC. KRISO is planning to test their 1 MW OTEC barge in equatorial waters that have a higher temperature differential than that near Korea in order to achieve closer to the designed net output. Japan is wanting to increase its Okinawa OTEC power output to 1 MW. Global OTEC is working on a 1.5 MW floating platform to be installed in Sao Tome and Principe.

The common perception is that OTEC technology is at the stage of building small 1-2 MW pilot plants with “proven” technologies in order to demonstrate its readiness. At Sea Solar Power, we remember when mini-OTEC accomplished those milestones in 1979 and do not see the need to repeat them. We also believe that by adapting barges, heat exchangers and turbines designed for other industries and thus “proven,” an OTEC plant cannot be made to operate as efficiently as needed to be economically viable.

An Ocean Energy Systems 2021 study concluded that the maximum size cold-water pipe that is currently feasible is 13 feet in diameter. Using “proven” technology the maximum power generated with this pipe diameter is 10 MW.3 Our SSP design also uses a 13-foot diameter cold-water pipe, but due to its efficient, unique design of the cycle, heat exchangers, and proprietary propylene turbine, we predict a net output of 20 MW, expandable to a maximum of 30 MW with maximum flow velocity through the pipe.

Sea Solar Power is designing its 20 MW floating plant using full-size turbines and heat exchangers that would be identical to those used in plants from 10 to 50 MW. We believe that today, even as Dr. David Mayer claimed in 1977, Sea Solar Power has the most viable design for a commercial OTEC plant. We are actively seeking opportunities to demonstrate this to the world.

32021 White Paper Ocean Thermal Energy Conversion OTEC, Martin G. Brown, Ocean Energy Systems

Acknowledgments

J. Hilbert Anderson

J. Hilbert Anderson continued working full-time in Sea Solar Power until passing away at age 95, having carried the baton of OTEC forward for over 40 years and generating 127 patents. His son, James H. Anderson, Jr, who began working on OTEC in 1962 with his father, continues to lead the work forward with the Sea Solar Power team. James H. Anderson, III, who like his father is a graduate of MIT, is the third generation to take up the baton of OTEC.

There have been numerous other researchers and proponents of OTEC besides the Andersons. Notable contributors have been Bryan Beorse (University of California), Dr. Clarence Zener (Westinghouse), Dr. Abraham Lavi (Carnegie Mellon), Dr. William Heronemus (Univ. of Massachusetts), Dr. William Avery (Johns Hopkins’ Applied Physics Lab), Dr. Robert Cohen (Department of Energy) Dr. C. B. Panchal (Argonne National Laboratory), Dr.’s John Craven, Luis Vega, and Hans Krock (University of Hawaii), Martin Brown (Ocean Energy Systems), Dr. Haruo Uehara (Saga University), Dr. Hyeon-Ju Kim (Korea Research Institute of Ships and Ocean Engineering) and Makai Ocean Engineering of Hawaii.